[ Welkom ] [ Het waarom ] [ Examens ] [ Morse sectie ] [ QTH Locator ] [ Lijsten / Tabellen ] [ Documenten ] [ Link Sectie ]

[ Welkom ] [ Het waarom ] [ Examens ] [ Morse sectie ] [ QTH Locator ] [ Lijsten / Tabellen ] [ Documenten ] [ Link Sectie ]

Squeeze-Keying Explained

Inleiding

The following article is partly based on the excellent report All about squeeze-keying by Karl Fischer (DJ5IL). However, while DJ5IL focuses on the historical context, the hardware used, and provides an in-depth technical explanation of the pros and cons of various modes, this article focuses on the "squeeze" technique itself.

The book Amateurfunk-Morsetelegrafie CW (DJ6HP), delves deeper into this, but the examples provided in this book (in my opinion) are unclear.

The examples mentioned in this article, such as Ü and Ä, are not the most practical for signaling but have been chosen purely for the purpose of explaining and understanding the "squeeze" technique.

1. Basic Concept: Memory Keyer

memory keyer is an electronic device that remembers a paddle that was pressed too early or released too soon and generates the corresponding dot or dash at the correct time. This means that when you’re sending CW, you don’t have to worry about exactly when to press the paddle:

a. Without memory, you need to press at the exact right moment.

b. With memory, you can release the paddle a bit earlier because the keyer "remembers" the signal and plays it back correctly later.

c. This increases timing tolerance and makes error-free sending easier, especially at higher speeds.

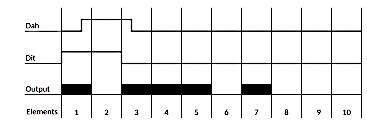

A standard memory keyer can be used with, for example, a side-swiper or a dual paddle. With a side-swiper, you operate one paddle back and forth without automatic dot/dash generation. With a dual paddle, each paddle can trigger its own element (dot or dash). See Examples 1–3.

Dashes are generated as full elements with spacing.

The dot paddle starts a series of dots; no automatic alternation.

The timing of alternation is important.

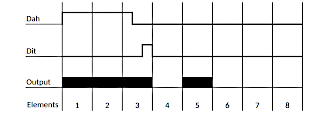

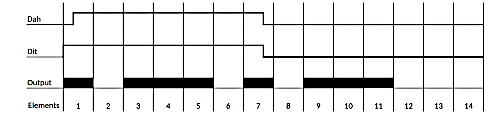

Example 1 — N (-.): One press on the dash paddle (-), followed by one press on the dot paddle (.). This example highlights that a dual paddle works well even without squeeze: left = dot, right = dash, and the keyer creates properly delimited elements.

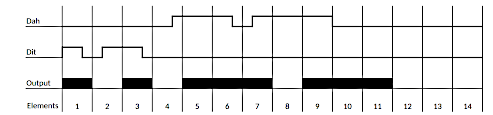

Example 2 — Ü (..--): Tap the dot paddle twice (left) for the two dots, then tap the dash paddle twice (right) for the two dashes. The keyer handles the element spaces; you switch paddles manually. This shows that there’s no automatic alternation: each element is started individually.

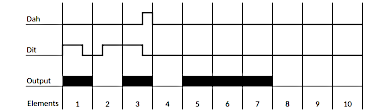

Example 3 — U (..-): Two quick taps on the left (..), followed by one tap on the right (-). The pattern sounds even because the keyer manages the length of dots/dashes and the spaces. You don’t have to "guess" the length, only the timing of starting each element.

2. De Ultimatic Mode

Operation: Ultimatic has both dot and dash memory. When you press both paddles, the keyer repeats the last chosen element. See Examples 4–5 for typical patterns and the "last paddle wins" behavior.

Starts with a dash; squeeze for two dots; ends with a dash.

"Last paddle wins": the last pressed paddle keeps repeating.

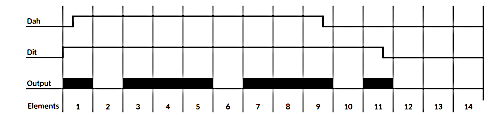

Example 4 — X (-..-): In Example 4, the letter X is sent. The sequence is as follows:

1. Press the dash paddle for the first dash.

2. Squeeze both paddles (squeeze) for the two dots in the middle. Since you last pressed the dot paddle, you hear dots.

3. Release the dot paddle to get a dash at the end.

4. Release the dash paddle.

You "send" the sequence that keeps going by your last paddle choice.

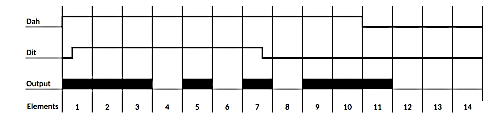

Example 5 — P (.--.): Start with a dot (dot paddle), then squeeze both paddles to activate the dash sequence (last paddle = dash) and get two dashes. Finish with a dot by quickly pressing the dot paddle and releasing the dash paddle. Ultimatic is forgiving: as long as your last choice is correct, the keyer follows suit.

3. De Iambische Mode

Origin: 1967 (Harry Gensler jr., K8OCO). "Iambic" (from poetry) means: alternation.

Operation:One paddle = a series of dots or dashes. Both paddles pressed simultaneously = alternating dot/dash, starting with the first paddle touched. In practice, we distinguish Type A (Curtis) and Type B (Accu).

4. Iambic A (Curtis-keyer)

Alternation starts with the first touched paddle.

Dot memory gives wider timing tolerance.

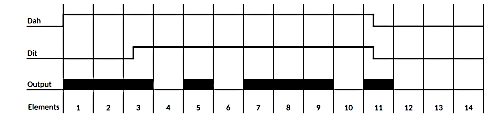

Example 6 — C (-.-.): Touch the dash paddle first (start with "-"), squeeze both paddles to alternate (".-.-"), and release as soon as "-.-." is complete. In Type A, no extra elements are added after releasing: it stops neatly at the last completed element.

Example 7 — Ä (.-.-): Start with a dot, squeeze to alternate, and release after four elements. Thanks to the dot memory in Type A, the timing feels relaxed: even if you release just after the boundary, no extra element is added.

Practical Note: Type A is ideal for learning squeeze. You focus on the pattern; the keyer tolerates small timing errors.

5. Iambic B (Accu-keyer)

Dot and dash memory; holding down adds extra elements.

Tighter window; more sensitive to errors when squeezing.

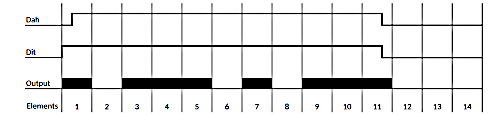

Example 8 — C (-.-.): In Type B, both dot and dash touches are remembered. If you hold down a paddle slightly too long between two elements, the keyer will already insert the next opposite element. This allows for very fast alternation—provided your timing is tight.

Example 9 — Ä (.-.-): The same principle: the alternation is fast, but releasing too late can add an extra dot or dash.

Practical Note: Type B is faster for advanced operators but more sensitive to timing errors.

6. Automatic Pause Extension

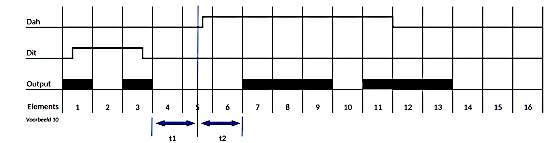

Activates when t1 > t2; corrects character spacing.

Example 10 — pause Extension: DThe keyer ensures readability by extending the pause between elements/letters when your actual pause (t1) is longer than the set reference (t2). Practically: if you accidentally pause just a bit too short, the keyer prevents two characters from "sticking together."

7. Other Timing Variants

Many keyers offer options like: dit/dah memory, dit-only or dah-only memory, iambic without memory, Curtis A with filters, and Accu-keyer with adjustable windows. The difference mainly lies in when memory is activated and how long it stays active.

8. Curtis vs Accu timing

At ~30 WPM ≈ 0.04 s/element; releasing within ~0.2 s prevents extra elements.

Shorter window (~0.08 s); stricter and more error-sensitive.

Releasing too late turns A into R (undesired extra element).

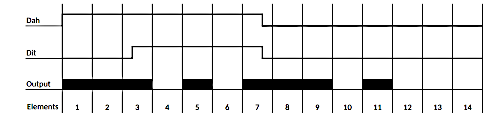

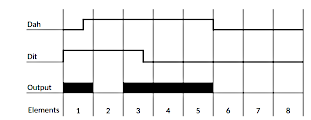

Example 11 — A in Curtis (.-): In Type A, memory is activated with a status change (touching/releasing). At 30 WPM, one element lasts about 0.04 s. If you release both paddles within ~0.2 s after the first element, no extra elements will be added. This makes Curtis feel tolerant of timing errors.

Example 12 — A in Accu (.-): In Type B, the window in which you must release is much shorter (~0.08 s) at 30 WPM. If you hold a paddle too long or release just a bit too late, the keyer may schedule an extra dot or dash via the active memory. This makes the mode fast but also critical.

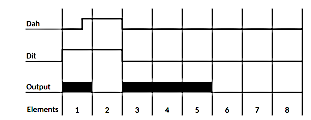

Example 13 — Error case (.- → .-.): If you release too late in Type B while sending the letter A (.–), the dot memory will add an extra dot, changing the pattern to R (.–.). This is the classic example of "holding too long" in Accu mode.

The Farnsworth Morse code Calculator provides good insight into how many seconds each element takes at a given WPM (Words per Minute).

9. Weighting

With a number of keyers (KIEL - CWMorse Pro Keyer/ k3ng_cw_keyer), you can adjust the "dot/dash weighting". This weighting setting determines how long or short the Morse characters are relative to the standard time unit.

The standard (ITU) Morse ratio is:

• 1 unit for a dot

• 3 units for a dash

• 1 unit for the pause between elements within a character

• 3 units between letters

• 7 units between words

Applying weighting also changes the sound character.

| Weight | Dot duration (in time units) |

Dash duration (normally 3x dot) |

Inter-element pause |

Result Sound character |

| 40% | 0.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | Short, staccato, “chopped” signal |

| 50% | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | Neutral – standard timing(ITU) |

| 55% | 1.1 | 3.3 | 0.9 | Slightly fuller – smoother Morse |

| 60% | 1.2 | 3.6 | 0.8 | Longer characters – sounds “fatter” |

| 70% | 1.4 | 4.2 | 0.6 | Very heavy – dashes sound long, short inter-element pauses |

Most operators choose a weighting between 50% and 60%, depending on personal preference, sending speed, and type of receiver.

Note: For a more detailed article about weighting, see the article Morse Weighting on this website.

10. Efficiency – Number of Keystrokes (Alphabet + Numbers)

The comparison below shows why electronic keyers are so efficient: fewer hand movements for the same alphabet/number set.

| Key Type | Keystrokes |

| Straight Key | 132 |

| Side swiper / cootie | 132 |

| Bug | 90 |

| Single paddle keyer | 73 |

| Iambisch | 65 |

Source:Iambic Sending Article (Chuck Adams - K7QO).

11. Summary

Overview of Keying Modes

| Mode | Developer / Year | Paddle Type | Logic Memory | Strength | Weakness |

| Ultimatic | W6SRY, 1953–1955 | Singel & Dual | Dot + Dash, Sequencing | Efficient, “last paddle wins” | Less common; takes getting used to |

| Iambisch (basis) | K8OCO, 1967 | Dual | No memory | Easy to learn alternation | Sensitive to timing errors |

| Curtis Type A | K6KU, 1969–1973 | Dual | Dot memory (status change) | Broad timing tolerance | Fewer "free" elements |

| Accu-keyer Type B | WB4VVF, 1973 | Dual | Dot & Dash memory (lasting impression) | Very efficient for advanced operators | Extra elements if held too long |

| Single paddle | Diverse | Single | N/A. | Simple, robust | Less efficient than squeeze |

| Straight key | Traditioneel | Single | N/A. | Simplicity, character | Slowest sending speed |

Note: For deeper historical context and (electro) technical details, see the article by Karl Fischer (DJ5IL).

Referenties/bronnen:

Amateurfunk-Morsetelegrafie CW (H.-J. Pietsch DJ6HP)

All about squeeze-keying (Karl Fischer DJ5IL)

Iambic Keying - Debunking the Myth (Marschall G. Emm - N1FN)

Iambic Sending Article (Chuck Adams - K7QO).

K1EL K16 - CW Morse Pro-Keyer

K1EL K16 - Manual

K3NG - Arduino CW Keyer

Wiki - Keyer